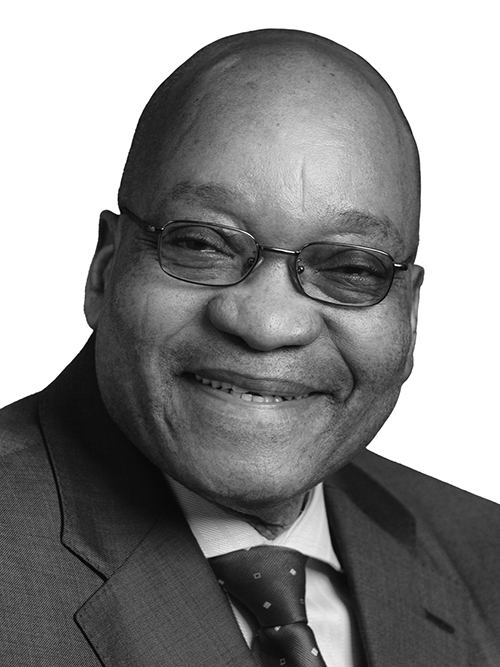

Speech by President Jacob Zuma on the occasion of the reburial of Mr and Mrs Klaas and Trooi Pienaar at Kuruman, Northern Cape Province

The Acting Premier of the Province of the Northern Cape, Grizelda Djikello,

The Deputy Minister of Arts and Culture, Dr. Joseph Phaahla,

Honourable MEC for Sport, Arts and Culture in the Northern Cape, Pauline Williams and other MECs,

The Representatives of the Government of Austria,

Representatives of the National Khoisan Council,

Leaders of the San and Khoi communities of the Northern Cape and South Africa,

Members of the Council of Traditional Leaders of South Africa,

Members of the Human Remains Repatriation Advisory Committee of the Minister of Arts and Culture,

Members of the Klaas and Trooi Pienaar Reference Group,

Members of the Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities,

Fellow South Africans,

We have gathered today, to close another painful chapter in our country’s history of colonial subjugation, racism and oppression.

We are here to correct a historic injustice, and restore the human dignity and citizenship of Mr and Mrs Klaas and Trooi Pienaar.

Our two compatriots are amongst a number of citizens of this country, who were violated in life and in death, by people who regarded them as not worthy of humane and decent treatment.

Our painful history tells us that more than hundred years ago, in 1909, a scientist from Austria, called Rudolph Pöch, went on a rampage in the greater Kuruman area, digging up bodies of dead people, destroying graves and disfiguring sacred art works, all in the name of science.

Mr Klaas Pienaar and his wife Trooi were farm workers on the farm Pienaarsputs near where we are today.

In May 1909, aged about 60 or 70, Mr Klaas Pienaar passed away after being sick for a month with malaria fever. In the first week of June 1909, his wife, Trooi Pienaar died, also due to malaria fever.

They were buried in the veldt on a farm at the instructions of their employer, the Griqua farmer Abel Pienaar. They left four children, who were temporarily taken into the care of Abel Pienaar.

The two were dug from their graves in October 1909, by an adventurer and grave robber Mehnarto, on the instructions of Rudolf Pöch.

We are told that Mr Pöch had been undertaking an expedition through southern Africa documenting and collecting Khoisan material culture, rock engravings and bodies.

Reports state that Mehnarto and his assistants wrapped the bodies with linen, cut them both at the knee joints, and forced them into a large barrel, which they filled with salt for preservation.

From there, Meharto proceeded to other farms and villages in the Kuruman district where he dug up and removed more bodies and skeletons. In some cases, he boiled the degraded bodies down to bone on the spot.

By the time the contents of Mehnarto’s wagon arrived for the train to Cape Town on 11 November 1909, it contained stolen rock engravings and 31 skeletons, at least five of them of freshly dead people, as well as the two bodies of Klaas and Trooi Pienaar.

From Cape Town, the bodies of the Pienaars and the other skeletons were illegally exported to Vienna.

Such behaviour is shocking and inexplicable. In African culture, and indeed in almost all cultures, very few things are regarded as sacred and worthy of profound respect as the dead.

We have deep respect for the dead because death is a fate awaiting all of us.

In death, all of us are vulnerable and dependent on other human beings to protect our dignity.

The bodies and skeletons sadly became part of the scientific collections of anthropology and material culture across a range of museums and institutions in Austria.

Rudolf Pöch was appointed at the University of Vienna as Austria’s first Professor of Anthropology, possibly as reward for what was then considered his exceptional work in Africa.

The truth about what happened in this area, has been uncovered thanks to research done by two Professors from the Department of History at the University of the Western Cape, Martin Legassick and Ciraj Rassool.

We are grateful to these two historians whose research produced a book called Skeletons in the Cupboard: South African Museums and the Trade in Human Remains, 1907-1917.

The book was published in the year 2000 by the South African Museum and the McGregor Museum, with assistance from the National Research Foundation.

In this book, Professors Legassick and Rassool share the painful history of a competitive trade in human remains, especially the remains of San Bushmen and women who were regarded then as ‘relics’ of an ancient anthropological and racial type.

The two scholars uncovered the evidence of an enquiry into the activities of Pöch and his assistant Mehnarto, undertaken by the Department of Justice during the period of the Union of South Africa government.

The enquiry probed the illegal digging out and exporting of bodies, skeletons and rock engravings.

The enquiry led to the country’s first law on heritage being passed, the Bushmen Relics Act of 1911.

However to add insult to injury, this law was passed not to protect the Khoisan people.

It was done simply because South Africa’s own museums and scientists had complained about the removal of the bodies and bones as they wanted to use them for their own experiments and exhibitions locally.

The work of these historians, and today’s reburial, forces us to confront the reality that in some of the museums in our country, there could be human remains collected largely from racist grave robbers.

This calls for urgent interventions to transform and decolonize South African museums, in the same manner that Austria is doing with their museums.

In Vienna in May 2008, at a conference held at the Natural History Museum to celebrate Pöch who had been regarded as an accomplished scholar, our Professors Legassick and Rassool outlined the brutal details of how Pöch’s human remains collection had been acquired.

We are pleased that subsequent to that presentation and engagements, the Natural History Museum of Austria committed itself to return the remains of Mr Klaas and Mr Trooi Pienaar to South Africa.

We are happy too, that the Austrian Minister of Science then authorized the formal removal of the remains of Klaas and Trooi Pienaar from the collection of the Austrian Academy of Science.

We take this opportunity to thank the Austrian government for taking this step and for working together with us to bring finality to this painful matter.

Working together with the government of Austria we are turning the tragic events that befell Mr and Mrs Pienaar into an opportunity for healing. It is also an opportunity to strengthen the bonds of friendship and solidarity between our two countries.

We therefore accept unconditionally, the apology expressed by the Austrian government for the actions of Rudolph Poch. Today, Mr and Mrs Klaas and Trooi Pienaar are no longer dehumanised objects of racial science and anthropology, to satisfy the curiosity of Mr Poch and his ilk.

They have been re-humanised and have regained their South African identity, 103 years after the tragedy that befell them.

Today, through this reburial, we are taking another step forward towards closing the chapter on the brutality of racism and its legacy in scientific practices and museum collections.

The democratic government remains determined to restore the right to human dignity, as in that way, we are reaffirming the humanity of all our people.

In 2002 we brought back the remains of Sarah Baartman who has been stripped of her dignity and Khoi-San identity. She had been shamelessly paraded throughout Europe for years and was treated with barbaric brutality.

Her remains were given a permanent resting place at the banks of the Gamtoos River where it will stand forever as a monument to the need to respect the humanity of others, and to eradicate racism and white supremacy.

Ladies and gentlemen,

The horrible treatment of Mr and Mrs Pienaar and others is a stark reminder of the need to comprehensively transform our museums and heritage sectors.

We are delighted to announce that processes are already underway to address the deep legacy of racial science in our museums.

Our museums must be transformed to become centres of heritage and expertise which respect all peoples and cultures. No museum must have a collection or material that depicts any section of the South African population as colonial objects, more so the indigenous people.

Therefore, all museums in South Africa need to urgently undertake an enquiry into the ethics of their human remains collection.

They must ensure that none of the material was collected through dehumanizing and racist methods.

The Department of Arts and Culture will work closely with the museum sector to ensure that this important national process takes place in accordance with national policy.

We have seen some positive action already. It is encouraging that Iziko Museums in Cape Town, one of South Africa’s national flagship museums, has already investigated the ethics of its collection.

The museum decided that all human remains bought from grave robbers or acquired for racial research were unethically collected and needed to be returned.

We congratulate Iziko Museums for subsequently removing from their collection, all unethically collected human remains.

Compatriots,

It has been a difficult and painful process to reach this point of laying our ancestors to rest in the country of their birth, where they were uprooted with no ability to defend themselves, as they were dead.

We are truly thankful to all parties in government, the museum and heritage sector, the universities and communities who have made it possible for us to be here to rebury them with the dignity they so truly deserve.

We are also thankful for the guidance of all the members of the Human remains Repatriation Advisory Committee for their emphasis on this being a project of rehumanisation.

We congratulate the scholars from the University of the Western Cape, Professors Martin Legassick and Ciraj Rassool. Their expertise in Northern Cape history and in the field of Museum and Heritage Studies has ensured that every stage of this rehumanisation process was premised on thorough research and the best international scholarship.

We are grateful to Professor Walter Sauer, formerly the head of the Austrian Anti-Apartheid Movement, for his comradeship and commitment to the people of Southern Africa. Our friends and comrades in the Anti-Apartheid movement stood with us as we fought for freedom.

We are happy that they stand with us still, as we rebuild the country and create a humane, caring, democratic, nonracial and non-sexist society.

We are grateful to the government of Austria and the leaders of the Austrian museum sector for walking this important road of healing with us.

We are thankful to the members of the families and communities of the Northern Cape, especially the members of the Reference Group for assisting and engaging with government to ensure that the return and reburial of Mr and Mrs Klaas and Trooi Pienaar would be dignified and treated with the significance that these processes deserve.

Finally, we are thankful for the lives of Mr and Mrs Klaas and Trooi Pienaar. We are delighted that we have been able to bring them home to be buried near their people.

Mr and Mrs Pienaar will now rest in peace on African soil. Through today’s reburial, their humanity is being reaffirmed and their dignity is being restored irreversibly.

May their spirit help the people of our country to overcome the pain of the past, and move together in harmony to build a better future.

I thank you.